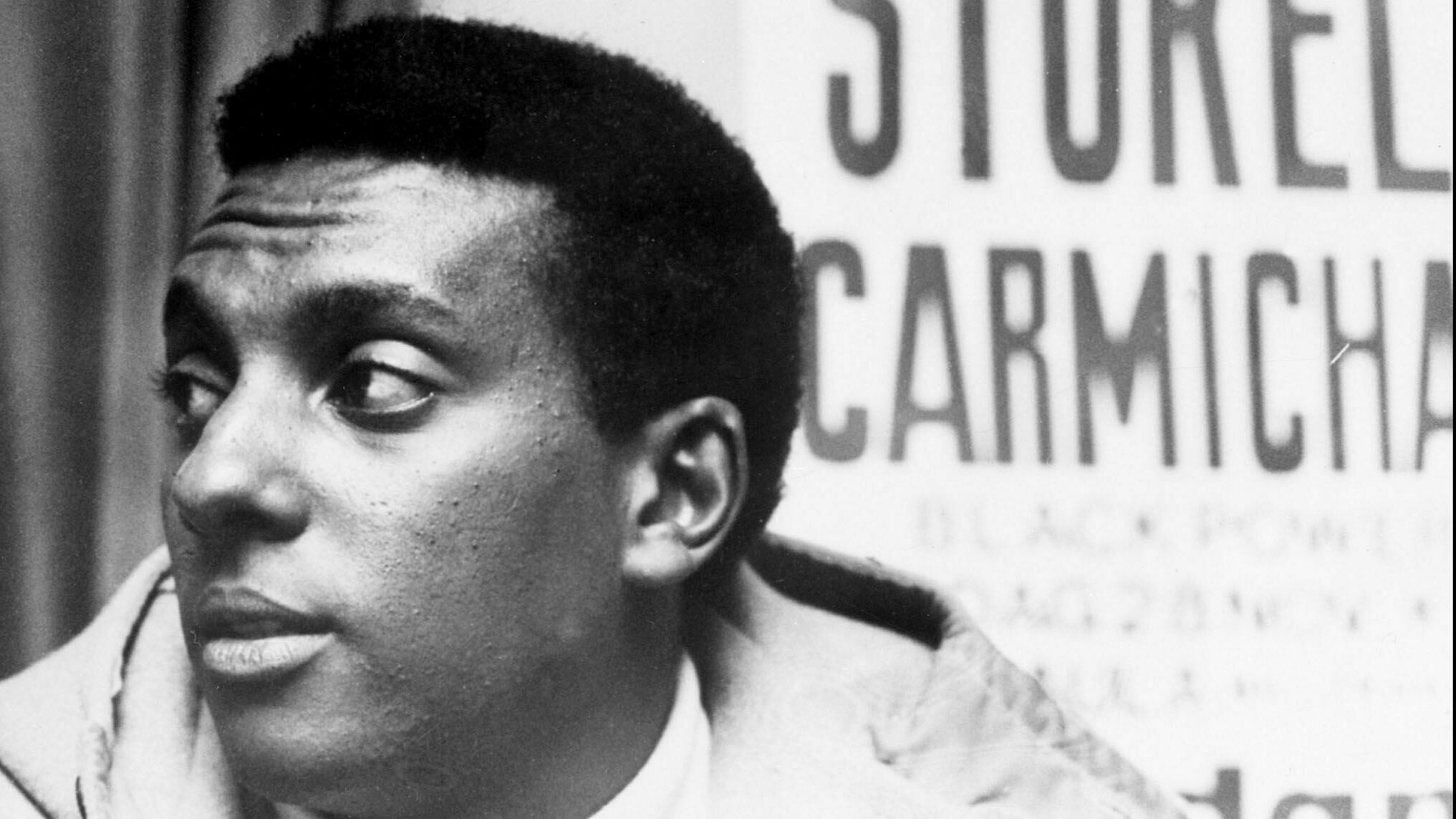

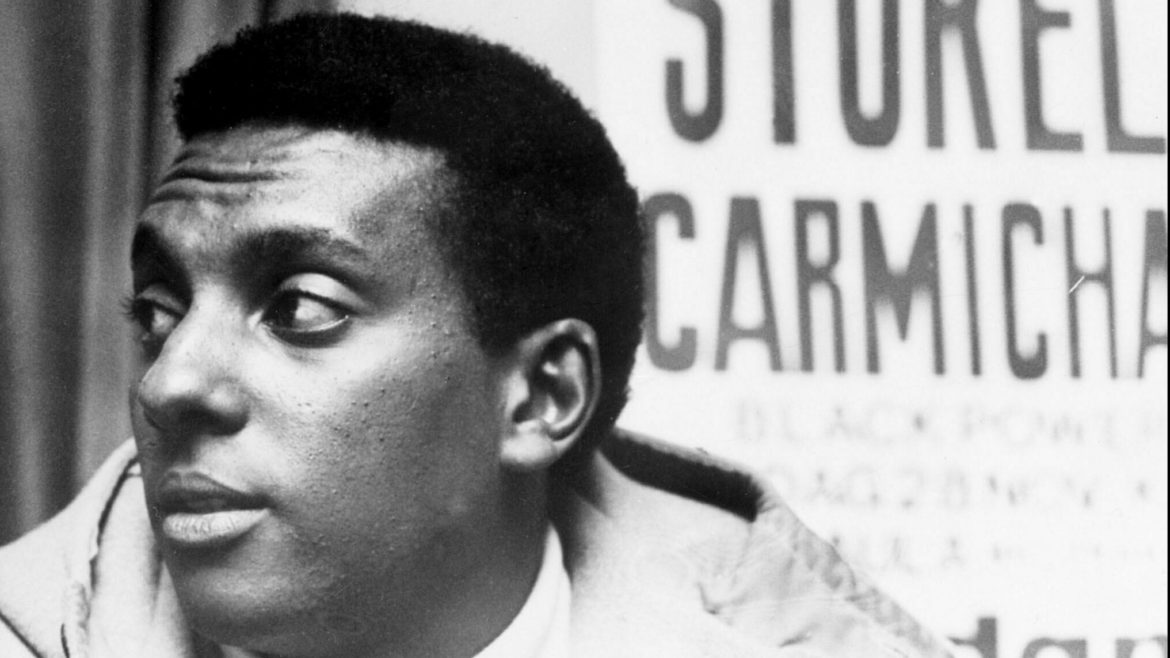

Journalist Mark Whitaker says that much of what’s happening in American race relations today traces back to 1966, the year when the Black Panthers were founded and the Black Power movement took full form. It’s also the year when when Stokely Carmichael replaced John Lewis as chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and challenged the tactic of non-violence.

“The next day [the chant] gets reported by the Associated Press,” Whitaker says. “The story gets picked up in 200 newspapers around the country, and all of a sudden, everybody’s talking about Black Power.”

Whitaker writes that it wasn’t just the language of the civil rights movement that changed in 1966. There was also an “awakening of Black consciousness on a cultural level,” he says. “It was really the year when Afros took off, when people started wearing dashikis, where a lot of young Blacks said, ‘We don’t want to be called Negroes anymore.'”

There was also a notable shift away from integration, Whitaker says. Carmichael advocated for Black people to create their own political party and to elect their own officials. As the leader of the SNCC, he expelled the group’s white members, leading to a drop in the group’s fundraising and political clout. All of this, Whitaker says, laid the foundation for the modern conservative movement — including the election of Ronald Reagan as governor of California in 1966 and George Wallace‘s presidential run in 1968.

“A big lesson of 1966 is, beware of the potential backlash,” Whitaker says. “I was writing this book in 2020 in the midst of all the marches that summer. … I see what happened in 1966 and what happened in 1966 tells me that there is going to be hell to pay. There’s going to be a big backlash to what looks like all this progress in 2020. And sure enough, that’s what we’re living with right now.”

Whitaker is the first African American to lead a national news magazine as editor of Newsweek. His previous books include Smoketown, My Long Trip Home and the 2014 biography Cosby, which was later widely criticized for not addressing multiple allegations that superstar comic Bill Cosby had drugged and sexually assaulted women. Whitaker has since acknowledged that it was a mistake to omit the allegations from his book, tweeting, “I was wrong to not deal with the sexual assault charges against Cosby and pursue them more aggressively.”

In terms of integration, what Stokely was saying about the South (vis à vis poor Blacks) and then later the Panthers were saying, even in the North (vis à vis urban Blacks in places like Oakland) … was that actually white people were not interested in integrating with poor Blacks in the South or in the North. That integration was sort of a project by middle-class Blacks for middle-class white people who might be willing to live side by side with their kind, with the Black middle class, but not necessarily with the Black poor and the Black underclass in the North.

The press portrayed Carmichael as [Martin Luther] King’s nemesis. But in fact, on a personal level, they got along quite well. Stokely had a lot of respect for Dr. King. Dr. King didn’t agree necessarily with all of Stokely’s rhetoric, but he admired the fact that he was an activist who had put his life on the line and going out to organize in the South. But there were both sort of differences that had to do with tactics and strategy, but also with background. So one of the things that was different about the Black Power leaders was some of them had come out of the South, but a lot of them came out of the North. So they were the children of the Great Migration. Their parents and grandparents had come north from the South. They had had educational opportunities that Blacks in the South didn’t necessarily have. Carmichael himself had gone to Howard University and before that to the Bronx High School of Science in New York, an elite high school. And they just didn’t have the sort of tradition of deference, frankly, that the older generation in the South had. They were less rooted in the church than the previous civil rights generation. So they just sort of had a different attitude. They were impatient. They had seen their parents’ dreams dashed when they came north in the Great Migration.

After Selma, he was famous and he used that fame to go around the country and also overseas to raise money for SNCC. So that was good for SNCC’s coffers, but it actually distanced him from a lot of the SNCC membership. And so he got out of touch with this increasingly militant mood that was taking shape in 1966. And that spring there was one of these periodic retreats that SNCC would have the entire membership … discuss strategy, but they would also elect officers for the next year. And Lewis had been in Europe, giving speeches, raising money. He arrives badly jetlagged to this retreat at a religious camp outside of Nashville, expecting that he’s going to be reelected. But a lot of the rank and file SNCC members at that point were upset with him for being too distant, too preoccupied with all of this travel, but also with still being too close to King, but actually, I think the issue was much more with LBJ. .. And this time Stokely wins. It crushed John Lewis. … This had been his identity. He grew up as a poor sharecropper for his young life. … We remember him now as the sainted congressman and beloved national figure. But that experience just completely crushed him. And it took a long time for him to recover.

I think it had two effects: One was on the way that SNCC was perceived by the outside world, particularly the white world. John Lewis was someone who was deeply respected by white journalists by people who gave money to SNCC. And once they learned that he had been removed, very precipitously, unexpectedly, it immediately sort of cast a shadow over the people who had ousted him. In other words, Stokely Carmichael and the new leadership group. They were immediately suspect in the eyes of a lot of people who supported John Lewis.

But the other effect was internal. John Lewis had always stood for the principle of SNCC being open to white membership. He had a lot of very close friends among some of the original white members of SNCC. And so that to the degree that, as 1966 progressed and the whole issue of white participation loomed larger and larger, and it eventually led by the end of the year to the expulsion of the last remaining white members of SNCC, I think if John Lewis had been there, he would have fought that very aggressively. And once he was gone, the door was more and more open to that happening.

In Watts, after the the Watts riots of 1965 in Los Angeles, there had been a group of local Black activists who had decided that they were going to ride around just looking out for situations where police, white police were interacting with the local Black population and just stand at a remove where the police could see them, but where they weren’t trying to interfere, but just to make their presence known. Like, “We’re watching this. So if anything gets out of hand, if the police in any way abuse their authority, we will be witnesses.”

And up in the Bay Area, in Oakland, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who were in a community college there at that point, they’re following all of this and Huey Newton … becomes aware that in California at the time, there were open carry gun laws. In other words, it was perfectly legal to carry arms in public as long as you could see them. And so his idea was that he was going to take what was going on in Watts a step further and form a community patrol, but with guns, so that he and Bobby Seale and others would ride around as keeping their eye on the local Oakland police. But as they were standing across the street or wherever they were, they would also be holding guns. It was not, in their mind, initially the idea that they were going to confront the police or enter into gunfights with them, but just let them know, “Hey, we’re here and we have an eye on you.”

I think that when people think of the Panthers today, they have an immediate visual image of Newton and Seale and others, they’ve grown out their hair and afros. They’re wearing these cool berets and leather jackets and so forth. … A big part of their appeal is they just looked very cool, at least to a lot of young Blacks in those days, and still today. And so they stood for a political project, but also an expression of Black identity, vis à vis the way they dressed and the way they looked and the way they spoke. And I think because in some ways that has been the more enduring legacy of Black Power, the cultural part of it, I think people just think like, “God, the Panthers were so cool.” And they were cool in some ways. But I think because they’re romanticized in that way. I think people have not really focused and studied enough about the lessons of what they tried to achieve politically. I think this is an object lesson for the Black Lives Matter movement: [The Black Panthers] were correct in a lot of their original analysis, certainly about issues with the police. We are still living with that very much almost on a monthly basis here in this country, tragically, also about the limits of integration. They just took the way in which they dealt with it to an extreme that ultimately just became self-defeating.

Transcript :

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Terry Gross. Much of what is happening in American race relations today traces back to the pivotal year of 1966, writes my guest, Mark Whitaker. He says it’s the year the Black Power movement took full form. Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the slogan Black Power, became chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as SNCC, and began to redirect SNCC’s focus from peaceful voter registration in the South to a more sweeping and radical agenda that questioned nonviolence, mainstream politics and white alliances. Whitaker says it’s also the year the Black Panther Party was founded and the year Martin Luther King struggled to bring his Southern, nonviolent, integrationist strategy to the urban North in Chicago. It was a year in which the Black Arts Movement flourished and the year of the first push for an African American studies program.

Black studies has special significance in Whitaker’s life. His father, Syl Whitaker, was the first chair of the African American studies program at Princeton University. He taught at other universities as well. Whitaker is the author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” He’s the former managing editor of CNN Worldwide, served as the Washington bureau chief of NBC News and was a reporter and editor at Newsweek, becoming the first African American leader of a national newsweekly.

Mark Whitaker, welcome to FRESH AIR. You know, it’s discouraging how the same battles are being fought today – police killing Black people, voting rights, Black studies programs. What’s your reaction to that?

MARK WHITAKER: Well, you know, Terry, that’s actually why I wanted to write this book. I started working on it about five years ago. The Black Lives Matter movement had become a real phenomenon. And it was a new movement, led by a young, Black generation focused around a symbol that was getting a lot of attention but that not everybody understood and that both challenged the white power structure but also questioned a lot of the agenda of the older Black establishment. And I was watching all of this unfold, and I was thinking, you know, this looks a little familiar. It looks a lot like the Black Power movement of the ’60s.

GROSS: So 1966, as you said, is the year the Black Power movement gets started. Stokely Carmichael made those words famous. That year, 1966, he was invited to a conference on Black Power and its challenges at the University of California, Berkeley. I want to play a short clip about why he’d become disillusioned with the civil rights movement’s emphasis on integration. And this is from his 1966 speech at Berkeley.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

STOKELY CARMICHAEL: Now, several people have been upset because we’ve said that integration was irrelevant when initiated by Blacks and that, in fact, it was a subterfuge – an insidious subterfuge – for the maintenance of white supremacy. Now, we maintain that in the past six years or so, this country has been feeding us a thalidomide drug of integration and that some Negroes have been walking down a dream street talking about sitting next to white people and that that does not begin to solve the problem, that when we went to Mississippi, we did not go to sit next to Ross Barnett. We did not go to sit next to Jim Clark. We went to get them out of our way – and that people ought to understand that, that we were never fighting for the right to integrate. We were fighting against white supremacy.

(APPLAUSE)

GROSS: That strikes me as a pivotal difference between the younger generation from the North and the older – but not that old – leaders in the South. Because in the South you had Jim Crow. I mean, there really was – you couldn’t go into restaurants, or you had to sit in the back of the bus. As much as there was actual segregation in the North, you could still go into places. I mean, you had – you didn’t have to drink from different water fountains and things like that. So this is a real split between the Black Power generation and the peaceful, nonviolent generation of civil rights leaders. Add to what Stokely Carmichael said about not wanting the emphasis to be on integration.

WHITAKER: So what Stokely realized, particularly after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, was that just registering Blacks in the South to vote really wasn’t going to get them that far, as difficult as that was. Why? Because those states were completely controlled by segregationist Democrats, the most famous of which we all know was George Wallace, who was the governor of Alabama. So Stokely’s position was, why should we register all of these Black folks to vote just to have to turn around and vote for white supremacists? So what he wanted to do was to organize – and what he started in Lowndes County, Ala., in ’65 and ’66 – was organizing Blacks to form their own political party. They could elect their own officials.

So in terms of integration, what Stokely was saying about the South, vis-a-vis poor Blacks, and then later the Panthers were saying, even in the North, vis-a-vis urban Blacks in places like Oakland where they came from, was that, actually, white people were not interested in integrating with poor Blacks in the South or in the North, that integration was sort of a project by middle-class Blacks for middle-class white people who might be willing to live side by side with their kind – with the Black middle class – but not necessarily with the Black poor and the Black underclass in the North.

GROSS: Carmichael popularized the phrase Black power. He wasn’t the first person to use it. One of his colleagues at SNCC was. But tell us how that phrase originated and what it was originally meant to mean.

WHITAKER: It was during the Meredith march in June of 1966. Stokely Carmichael had come down there with Dr. King and other leaders to carry on the march of James Meredith, the Black activist who had been shot by a white supremacist on the highway. And they were going from Memphis all the way to Jackson, Miss. In the middle of the march, at a nighttime rally, after spending the whole day in jail because he had been arrested for setting up tents in a Black schoolyard…

GROSS: With the permission of the school.

WHITAKER: …With the permission of the school. But the cops, the white, local cops arrested him anyway. Stokely gets out that evening just in time to come to speak at a rally. Five hundred local Black folks are assembled in a sandlot field in Greenwood, Miss. And he decides that rather than saying the chant that had become, you know, the rallying cry for the civil rights movement for years, which was freedom now – what do we want? Freedom now. Instead, he stands up, and he says, we’ve had enough of saying freedom now. He said, I’ve been to prison. This is the 27th time I’ve been to prison since I came down here to organize in the South. What we’re now going to chant is Black power. And then he says, we want Black power. And the crowd cries back, Black power. And he – again, he repeats it. We want Black power. They chant back, we want Black power. This goes on, back and forth, five or six times. And the next day it gets reported by the Associated Press. The story gets up in 200 newspapers around the country. And all of a sudden, everybody’s talking about Black Power.

GROSS: And when the press picks it up, some of the press interprets this as, this is racism of Blacks against whites.

WHITAKER: What the press immediately hears in the slogan Black Power are two things. One is violence – oh, what you’re saying is Blacks want to take power through violence. And the other was this is all Black. In other words, you’re talking about Black Power. There’s no room for white people. Now, as we’ll discuss, both of those things become more of a part of the message as time goes on. It becomes almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy. But at the very beginning, it was really the press reading those things into it as much as it was the original intent.

GROSS: 1966, the year that you write about in your book, is also a year of a lot of disputes within the civil rights movement – between, for instance, the Southern Christian Leadership movement and Martin Luther King and the younger people who want more power, more Black Power, as opposed to just, like, peaceful resistance. So let’s talk about some of those controversies. Why don’t you describe what some of those controversies were between the older generation and the younger generation? And again, when I say older generation – I mean, Martin Luther King was – how old was he when he died? – like, around 36?

WHITAKER: Thirty-nine.

GROSS: Thirty-nine, yeah. So when I say younger, it’s like the difference between, like, people in their 30s and people in their 20s. Everybody’s young in that movement.

WHITAKER: No. And actually, one of the things I write about in the book is that the press portrayed Carmichael as King’s nemesis. But in fact, on a personal level, they got along quite well. Stokely had a lot of respect for Dr. King. Dr. King didn’t agree necessarily with all of Stokely’s rhetoric. But he, you know, admired the fact that he was an activist who had, you know, put his life on the line in going out to organize in the South. But there were both sort of differences that had to do with tactics and strategy, but also with background.

So one of the things that was different about the Black Power leaders was some of them had come out of the South, but a lot of them came out of the North. So they were the children of the Great Migration. Their parents and grandparents had come north from the South. They had had educational opportunities that Blacks in the South didn’t necessarily have. Carmichael himself had gone to Howard University and, before that, to the Bronx High School of Science in New York, an elite high school.

And they just didn’t have the sort of tradition of deference, frankly, that the older generation in the South had. They were less rooted in the church than the previous civil rights generation. So they just sort of had a different attitude. They were impatient. They had seen their parents’, you know, dreams dashed when they came north in the Great Migration. So that was the difference in background. Then, of course, there were tactical differences as well.

GROSS: We need to take a break here, so let’s take care of that. If you’re just joining us, my guest is journalist Mark Whitaker. His new book is called “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” We’ll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF AHMAD JAMAL’S “THE LINE”)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let’s get back to my interview with Mark Whitaker, a journalist and author. His new book is called “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.”

John Lewis is a really interesting figure in 1966 ’cause he’s kind of in the middle here. You know, he’s kind of like a protege of Martin Luther King, but he is also, from around ’63 to ’66, the chair of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And 1966 is the year that he’s basically ousted from SNCC.

And Lewis had been one of the original Freedom Riders. He was a voting rights activist. He registered Black voters in the South. He was arrested many times. Everybody probably knows that he led one of the marches from Selma to Montgomery, and his skull was split open by police in Selma while marching over the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

So he’s kind of in the middle here because he’s allied with SNCC, which is becoming very disillusioned with mainstream politics and with the emphasis on integration. But his roots are with Martin Luther King and peaceful nonviolence and voting rights. So why was he ousted in 1966 from SNCC?

WHITAKER: You know, after Selma, he was famous. And he used that fame to go around the country and also overseas to raise money for SNCC. So that was good for, you know, SNCC’s coffers, but it actually distanced him from a lot of the SNCC membership. And so he got out of touch with this increasingly militant mood that was taking shape in 1966.

And that spring, there was a – one of these periodic retreats that SNCC would have. The entire membership, they’d take a week off. They’d all assemble at some place that they had been able to rent, you know, at a cheap cost. And they would discuss strategy, but they would also elect officers for the next year. And Lewis had been in Europe giving speeches, raising money. He arrives badly jet-lagged to this retreat at a religious camp outside of Nashville, expecting that he’s going to be reelected.

But a lot of the rank-and-file SNCC members at that point were upset with him for being too distant, too preoccupied with all this travel, but also with still being too close to King. But actually, I think the issue was much more with LBJ. And as one of them put it, you know, every time LBJ calls, you know, he rushes to send a suit to the dry cleaner and get on a plane to go to Washington.

So on the last night of the retreat, they have this vote. On the first ballot, he wins easily. But then people go off – start to go off, drift off, to go to sleep. A young SNCC member comes into the hall and says, oh, wait a second, wait a second. Not enough people voted. Because a lot of people were ambivalent and they had abstained.

Anyway, they force another vote. The debate goes on all night long. Finally, at the crack of dawn the next morning, they have another vote. And this time, Stokely wins. And it crushed John Lewis. You know, he said in his autobiography that he kind of knew that there was – Stokely he accused of plotting against him, other people, but he clearly did not see it coming.

This had been his identity. You know, he grew up as a poor sharecropper for his young life. And it really took him a decade to recover. You know, we remember him now as this sainted congressman and beloved national figure. But that experience just completely crushed him. And it took a long time for him to recover.

GROSS: Because he’d basically given his life to SNCC.

WHITAKER: He had – literally had almost died many times and gone to jail dozens of times for SNCC. And even the people who voted against him – one of the reasons they were so ambivalent is that even though they thought he was too mainstream, he was, you know, too interested in, you know, allying himself with King and with LBJ, nobody disputed his bravery.

GROSS: What did it represent within the civil rights movement that John Lewis was basically ousted from SNCC?

WHITAKER: Well, I think it had two effects. One was on the way that SNCC was perceived by the outside world, particularly the white world. John Lewis was someone who was deeply respected by white journalists, by people who gave money to SNCC. And once they learned that he had been removed very precipitously, unexpectedly, it immediately sort of cast a shadow over the people who had ousted him. In other words, Stokely Carmichael and the new leadership group – they were immediately suspect in the eyes of a lot of people who supported John Lewis.

But the other effect was internal. John Lewis had always stood for the principle of SNCC being open to white membership. He had a lot of very close friends among some of the original white members of SNCC. And so to the degree that, as 1966 progressed and the whole issue of white participation became – loomed larger and larger, and it eventually led by the end of the year to the expulsion of the last remaining white members of SNCC. I think if John Lewis had been there, he would have fought that very aggressively. And once he was gone, the door was more and more open to that happening.

GROSS: What were the consequences of, for instance, ousting the remaining white members of SNCC?

WHITAKER: Well, first of all, you lost people who themselves had actually given much of their young lives to SNCC. Bob Zellner and his then wife, Dottie, Dorothy Zellner, who were literally the last members – they had been among the first whites to join SNCC and were the last to be expelled. They had gone to prison, too. They had risked their lives, too. And they were incredibly committed. So you lost that.

But then you lost – you know, fundraising dried up. SNCC was largely funded by white donors. And press sympathy dissipated. And, you know, Clayborne Carson, the great Black historian at Stanford who wrote a book about SNCC – he also made the point, and I quote him in the book, that having white allies, particularly powerful white allies in various places in American society, but particularly in Washington and so forth, also provided a little bit of protection and a buffer against, for example, persecution by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. And once the sort of white supporters of the movement thought that there was no longer a place for them, they became a lot less interested in providing protection against what then became really rampant, which was a campaign by the FBI to investigate and to destabilize first SNCC and then later the Panthers.

GROSS: Well, let me reintroduce you again. If you’re just joining us, my guest is journalist Mark Whitaker, author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” We’ll be right back after a short break. I’m Terry Gross. And this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF LEE MORGAN’S “THE GIGOLO”)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Terry Gross. Let’s get back to my interview with Mark Whitaker, author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” Whitaker says 1966 is the year the Black Power movement took full form. Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the slogan Black Power, became chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee – SNCC – and began to redirect SNCC’s focus from peaceful voter registration in the South to a more sweeping and radical agenda that questioned nonviolence, mainstream politics and white alliances. It’s the year the Black Panther Party was founded, the year Martin Luther King struggled to bring his Southern, non-violent integrationist strategy to the urban North in Chicago. And it was a year in which the Black arts movement flourished.

I want to talk with you about the Black Panthers, but first I want to talk with you about the origin of the Black Panther name. It goes back to Stokely Carmichael. When he was working to register Black voters in Alabama, he co-founded a political party there, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. This was a Black party with the goal of electing Black people to local offices like sheriff.

Under Alabama law, each party had to use an animal to represent the party on the ballot for the sake of people who couldn’t read. So the Lowndes County party chose the Black Panther, which inspired the name the Black Panther Party, which was founded in 1966. So here’s a clip of Stokely Carmichael speaking at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1966 about why they chose Black Panther as the symbol for this all-Black party in Lowndes County.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

CARMICHAEL: In Lowndes County, we developed something called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. It is a political party. The Alabama law says that if you have a party, you must have an emblem. We chose for the emblem a black panther, a beautiful black animal which symbolizes the strength and dignity of Black people, an animal that never strikes back until he’s backed so far into wall, war, he’s got nothing to do but spring out.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: Yeah.

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: Yeah.

CARMICHAEL: And when he springs, he does not stop.

(APPLAUSE)

CARMICHAEL: Now, there is a party in Alabama called the Alabama Democratic Party. It is all white. It has as its emblem a white rooster and the words white supremacy for the right. Now, the gentlemen of the press, because they’re advertisers and because most of them are white and because they’re produced by that white institution, never calls the Lowndes County Freedom Organization by its name, but rather they call it the Black Panther Party. Our question is, why don’t they call the Alabama Democratic Party the white cock party?

(CHEERING)

CARMICHAEL: It’s fair to us. It’s fair to us.

GROSS: Informative and funny.

WHITAKER: Yeah. Actually, I’ve got to say – and I’m glad you play that clip because, you know, you can go back and quibble with some of Stokely’s more extreme rhetoric, but he was a very, very charming and very, very funny guy. And it’s one of the reasons why he had so much support, both within SNCC in that era and more broadly, among Black people in those days.

GROSS: So how did that speech and the publicity for that speech lead the founders of the Black Panther Party, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, to name their movement after this emblem used in Lowndes County?

WHITAKER: So that speech was given in Berkeley in October of 1966. It was – a conference had been organized by white organizers from the Students for a Democratic Society. And in anticipation of that speech, they brought some of the pamphlets that had been prepared for the campaign down in Alabama to the Bay Area. And so they were circulating around the Bay Area. Now, there are various stories about how Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who founded the Black Panthers – when they first saw the symbol. But there’s absolutely no question that the panther that we now mostly associate with the West Coast Black Panthers, with their berets and leather jackets and guns, was the very same panther that had been adopted – and the drawing of the panther. All of that was taken wholesale from this small would-be party in rural Alabama and transplanted onto this new Black Panther Party for Self-Defense of folks who had grown up in the ghettos of the North and the West.

GROSS: So the Black Panthers not only appropriate the emblem of the Black Panther from the Lowndes County party that Stokely Carmichael was very active in founding, they were also very inspired by Stokely Carmichael and by his rhetoric. But the Panthers take militancy a step further. Its first goal was to protect against police violence and to protect it with armed groups. How did that approach start?

WHITAKER: So it was not a totally original idea. In Watts, after the Watts riots of 1965 in Los Angeles, there had been a group of local Black activists who had decided that they were going to ride around just looking out for situations where police – white police – were interacting with the local Black population and just stand at a remove where the police could see them, but where they weren’t trying to interfere, but just to make their presence known. Like, you know, we’re watching this, so if anything gets out of hand, if the police in any way abused their authority, we will be witnesses.

And up in the Bay Area, in Oakland, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who were in a community college there at that point – they’re following all of this. And Huey Newton decides – and Huey Newton was sort of this interesting, self-taught figure. He spent his – a lot of his spare time reading all sorts of things, but among them, law books. And he becomes aware that in California at the time, there were open-carry gun laws. In other words, it was perfectly legal to carry arms in public as long as they – you could see them.

And so his idea was that he was going to take what was going on in Watts a step further and form a community patrol, but with guns, so that he and Bobby Seale and others would ride around as keeping their eye on the local Oakland police. But as they were standing across the street or wherever they were, they would also be holding guns. It was not, in their mind initially, the idea that they were going to confront the police or enter into, you know, gunfights with them, but just let them know, hey, you know, we’re here, and we have an eye on you.

GROSS: Do you think they were effective in stopping police violence or, you know, diminishing police violence? Or do you think the police became more violent in reaction to the armed resistance?

WHITAKER: Well, what happened was that – you know, in the first weeks of their patrol, they did actually show up, and they were – you know, watched the police as they were interacting with folks on the street. And the police sort of gave them the evil eye, but there were no confrontations. But the other big thing that happens very quickly by the end of 1966 with the Panthers is that Eldridge Cleaver is released from prison. Eldridge Cleaver, who, you know, had a very different story and had been imprisoned for rape, but started writing these prison essays that got published in Ramparts magazine – and then, there was a whole movement among writers and activists to get him released.

He – as soon as he gets out, he starts covering the Panthers for Ramparts and then asks to join them. And once Eldridge Cleaver comes – becomes involved, he starts talking about, you know, a much more militant, much more violent project of armed revolution. And not long after that – and this is all a year later, in 1967 – Huey Newton gets involved with an incident where a white cop ends up being shot and dies. He ends up going to prison for that for several years. Bobby Seale famously gets caught up by 1968 in what is now known as the Chicago Seven trial – but the Chicago – initially, the Chicago Eight trial in Chicago – around the convention in 1968.

So there’s this vacuum that’s created because the original founders are in jail, and Eldridge Cleaver sort of takes over. And once he does, the Panthers get associated with this idea of armed revolution as opposed to local – you know, interactions with the local police. And that makes them just a much bigger and more inviting target for the FBI. So things go off the rails with the Panthers pretty quickly, and Eldridge Cleaver has a lot to do with that.

GROSS: And some of the Panthers are shot by the police.

WHITAKER: Yeah, yeah. No, no. Look, I mean, they were definitely being persecuted – I mean – or being – you know, at the local level and then at a larger level. So, you know, there’s a – after King is associated (ph), Cleaver decides that he is going to, in protest, lead an armed assault on a local police station in Oakland. A gun battle ensues. Another of the original founders of the Panthers, Bobby Hutton, is killed. It was one of the things that really broke – it was the final straw for Huey Newton. Huey Newton was in jail, but Bobby Hutton was like a younger brother to him. And once he felt that Eldridge Cleaver had caused his death, it was really over between Newton and Cleaver.

GROSS: Well, let’s take another short break here. If you’re just joining us, my guest is journalist Mark Whitaker. His new book is called “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” We’ll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MARVIN GAYE SONG, “INNER CITY BLUES (MAKE ME WANNA HOLLER)”)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let’s get back to my interview with journalist Mark Whitaker, author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.”

One of the things I like so much about your book is how it traces so many of the conflicts within the civil rights movement and within, like, the Southern and the Northern parts of the movement and how each generation of leaders kind of changes the movement. What do you think is the legacy of the Black Panthers?

WHITAKER: Well, you know, it’s interesting because the other thing I talk about a lot in the book is sort of the awakening of Black consciousness on a cultural level that happened in 1966. So it was really the year when Afros took off, when people started wearing dashikis, where a lot of young Blacks said, we don’t want to be called Negroes anymore. And I think that when people think of the Panthers today, they have an immediate visual image. And, you know, as I said, it’s of Newton and Seale and others. You know, they’ve grown out their hair into Afros. They’re wearing these cool berets and leather jackets and so forth. And they just – it was a big part of their appeal, is they just looked very cool at least to, you know, a lot of young Blacks in those days – and still today.

And so they stood for a political project, but also a – you know, an expression of Black identity vis-a-vis, you know, just the way they dressed and the way they looked and the way they spoke. And I think because, in some ways, that has been the more enduring legacy of Black Power, the cultural part of it, I think people think – they just think, like, God, the Panthers were so cool. And they were cool in some ways.

But I think they – because they’re romanticized in that way, I think people have not really focused and studied enough about the lessons of what they tried to achieve politically. And again, this is, I think, an object lesson for the Black Lives Matter movement. They were correct in a lot of their original analysis, certainly about issues with the police. We are still living with that very much, almost, you know, on a monthly basis here in this country, tragically – also about the limits of integration.

But they just took the way in which they dealt with it, you know, to an extreme that ultimately just became self-defeating.

GROSS: Well, you say it ended in, like, a political backlash, kind of paving the way for Ronald Reagan to become governor of California, getting more Republicans elected to the House, to Congress and eventually helping to pave the way for Nixon to become president.

WHITAKER: Yes. And 1966, quite apart from everything that I write about in terms of race relations, was a turning point in American politics. You begin to see, really, the foundation of the conservative movement that really has been dominant ever since, both the Reagan revolution – he’s elected governor for the first time, and largely thanks to a white backlash vote, in 1966 – but also, what was – what happened in the South that year, with the election of Lester Maddox as governor, the segregationist in Georgia, and also George Wallace succeeding. And he was term limited. He convinced his wife, who was a complete novice, to run in his stead. And she won in a landslide – that’s how.

And so he becomes, as a result of that, even more of the figure, runs for president in 1968. So – and in Wallace, you see, really, the germ of the sort of Trump white – more kind of white nationalist phenomenon that really is so dominant in Republican politics and conservative politics today. So a big lesson of 1966 is, beware of the potential backlash.

I was writing this book in 2020, in the midst of all the marches that summer. And people, when they would hear that I was working on this book, would say, oh, wow, it’s so timely, you know? This is, you know – and I would say, well, just wait, because I’m living with this. I see what happened in 1966. And what happened in 1966 tells me that there is going to be hell to pay. There’s going to be a big backlash to what looks like all this progress in 2020. And sure enough, that’s what we’re living with right now.

GROSS: What do you see as being the backlash now?

WHITAKER: Well, you know, I think you see it in what’s happening in Florida, Ron DeSantis’ war on what he characterizes as critical race theory, even on teaching Black studies in high school, a new wave across the country of voter suppression initiatives, largely aimed at people of color. You know, in 2008, Barack Obama was elected president. A lot of people were talking about a post-racial America. And look; it represented a historic breakthrough that a lot of people thought would never happen. But it also, at least in some parts of the country, actually accelerated new efforts to suppress the Black vote. And look; you know, we’ve seen this throughout our history. The advances of Reconstruction begat the age of Jim Crow and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

GROSS: So if we assume there’s going to be a backlash, I mean, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t stand up for your rights.

WHITAKER: Not at all. Not at all. Not at all. It just means you should be prepared for it.

GROSS: Well, let’s take another break here. If you’re just joining us, my guest is Mark Whitaker, author of the new book “Saying Out Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.” We’ll be right back after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF GERALD CLAYTON’S “SOUL STOMP”)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let’s get back to my interview with journalist Mark Whitaker, author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.”

I want to talk with you about Governor Ron DeSantis’ attack on African American studies in Florida. I mean, he’s attacked a lot of things in education, censoring certain books. He has the anti-woke act, in which you’re not allowed to teach, at certain grade levels, anything pertaining to homosexuality or gay rights are being queer. So DeSantis has banned the advanced placement Black studies program in Florida. He banned it after a draft was leaked of the curriculum for African American studies that was drawn up by the College Board.

And on February 1, the College Board released the official curriculum. And it had removed – maybe in response to all the pushback from DeSantis, it removed some of the subject matter that DeSantis had criticized, like certain Black writers and scholars associated with critical race theory or being queer or Black feminism, the Black Lives Matter movement. It added Black conservatism as a possible research subject.

You have a special connection to this in two ways. One is 1966, the subject of your book is the year that there’s the first push for Black studies programs at the college level. And also, your father was the first chair of African American studies at Princeton University. So I’m wondering, given all the background you have in this, what your reaction is to DeSantis banning of Black studies in Florida and the College Board’s revision of its curriculum?

WHITAKER: Well, again, here, I think it’s useful to actually look – go back and look at the origins of all of this. I mean, DeSantis is treating Black studies as, essentially, a sort of a conspiracy to make white – young white people feel bad about their privilege and their heritage. Whereas, in fact, originally, in 1966, the first advocates of Black studies were really focused on Black folks. They thought Black folks didn’t know enough about their own history and that part of this, you know, new emerging Black consciousness was to learn more about that and to embrace it.

It was also an alternative, frankly, to recruitment by Eldridge Cleaver and the, you know, people who wanted them, the young people, to be taking up arms on campus or previous nationalists who had said that Black people had to go to Africa or the Caribbean and establish a new homeland. So it was actually sort of a way of allowing Black folks to sort of feel more in touch with their identity and their background and their history but by remaining here in the United States.

And, you know, I still think that’s important. I mean, I think that, you know, history should both be sort of an educational purpose, but it also should serve a civic purpose by making people of all backgrounds understand their own role and their group’s role in the history, not the exclusion of anybody else’s role, and that that, you know, makes them better citizens and more committed to the future of this country.

GROSS: You know, while we’re on the subject of African American studies, you are African American. But, you know, it’s kind of funny in the sense that you’re biracial. Your father was Black, and your mother is the person who has actually more direct African roots. She’s white. She grew up in her early years in Cameroon, where her French parents were missionaries. So it’s – like, heritage in America is just, like, endlessly interesting.

WHITAKER: And I agree with that – and identity. And obviously, given…

GROSS: And identity. Yes, exactly.

WHITAKER: I mean, given my own personal history, it’s a subject that, you know, I have been thinking about my whole life and that, in one way or another, I’ve written about in all the books I’ve written. You know, my father – and again, I wasn’t necessarily thinking about this when I started this project, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot since then. You know, my parents got divorced in 1963. I was 6 years old. I saw my father the following summer. But then, for about five years, he dropped out of our lives.

And then, he resurfaced, as you said earlier, as the – he had just taken this job as the first director of African American studies at Princeton, a newly formed department. And all of a sudden, my dad has grown an Afro. And he’s wearing a dashiki. And he teaches me the Black Power handshake. And so since he was, obviously, my – even though he hadn’t been around – my primary model of male identity and Black identity, you know, I witnessed this transformation that, for me, was very sudden because I hadn’t seen him in a while.

And again, as I say, we’ve talked a lot about the politics of Black Power. But actually, I think that the clear, enduring legacy of it is as much cultural. And I interviewed a former Newsweek colleague named Vern Smith, who grew up in Natchez, Miss., but then went – was a student at San Francisco State when they started protesting for Black studies. And he describes what happened to him and his friends in college at that era – Black friends. He said it was like a born-again experience. He said, we were no longer Negroes.

Now, think about that. I mean, think about just, within the space of a year or two, this shift in consciousness, to think about yourself in a completely different way. And, you know – and that went, in my opinion, well beyond the politics. It was really an issue of, like, how do we think about ourselves? Who are we? What do we call ourselves? How are we allowed to be in the world? How are we allowed to dress? How do we interact with each other and not just white people? It was revolutionary, and it really changed everything. And I think Black America was never the same afterwards.

GROSS: Mark Whitaker, thank you so much for talking with us.

WHITAKER: Oh, thank you so much for having me.

GROSS: Mark Whitaker is the author of the new book “Saying It Loud: 1966 – The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement.”

Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, we’ll talk about the new documentary “All the Beauty And The Bloodshed.” It focuses on world famous photographer Nan Goldin, whose early photos were considered transgressive, but they were just about her friends – drag queens, gays and lesbians, underground artists, heroin users. A few years ago, she started a campaign and a series of protests demanding that museums stop taking financial donations from the Sackler family and remove the Sackler name from museum walls. The Sacklers owned Purdue Pharma, which manufactured and unscrupulously marketed OxyContin, leading to the opioid epidemic. Goldin got addicted after it was prescribed to her while recovering from surgery. We’ll talk with Goldin and the film’s director, Laura Poitras. I hope you’ll join us.

(SOUNDBITE OF AARON GOLDBERG’S “ISN’T THIS MY SOUND AROUND ME”)

GROSS: Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, Sam Briger, Lauren Krenzel, Therese Madden, Ann Marie Baldonado, Thea Chaloner, Seth Kelley, Susan Nyakundi and Joel Wolfram. I’m Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF AARON GOLDBERG’S “ISN’T THIS MY SOUND AROUND ME”) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

9(MDQ0ODU2MzU2MDE1NTM3MTIwMjFiMDhjNA000))