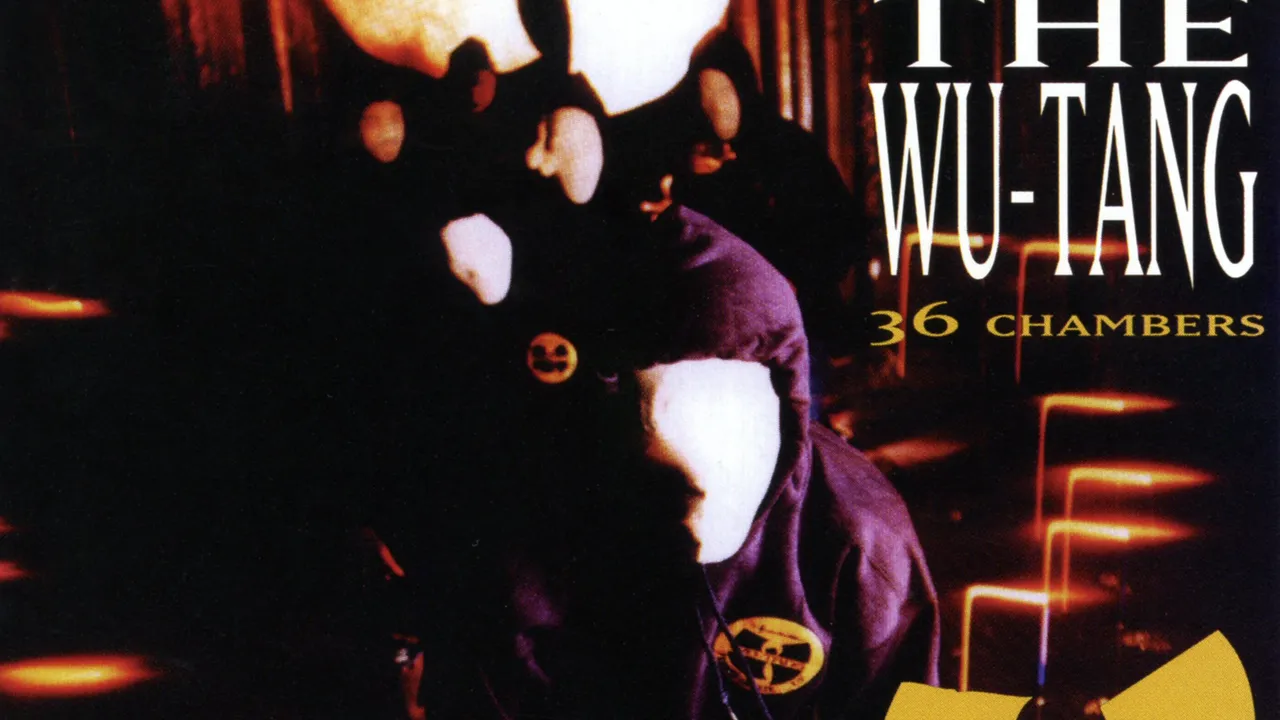

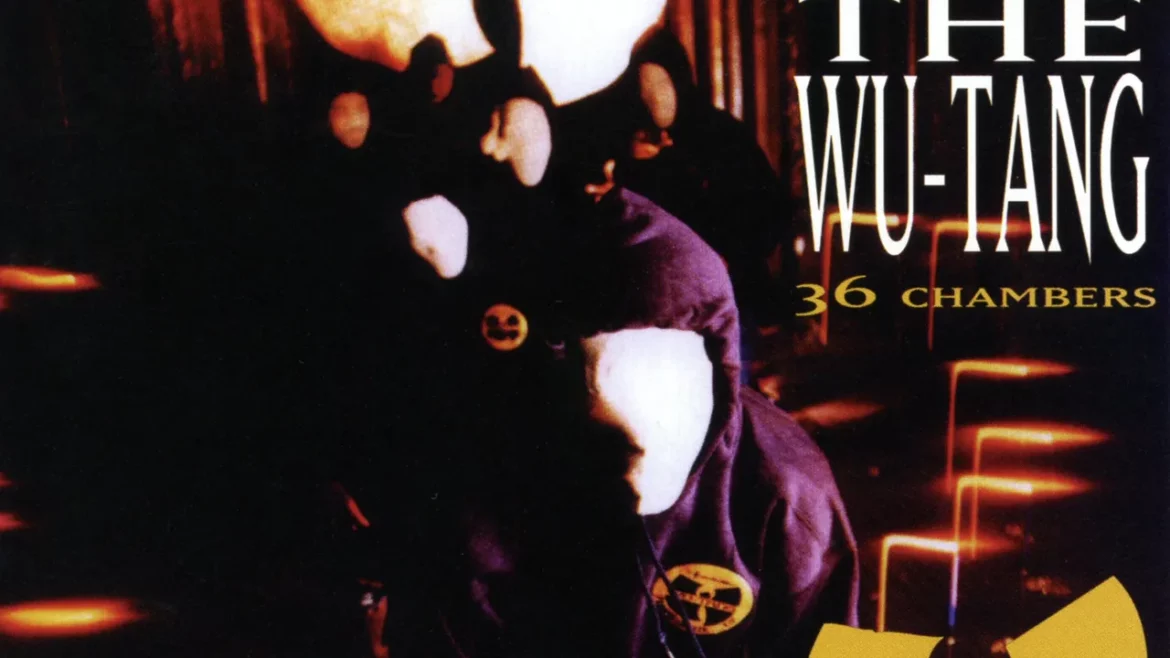

In the landscape of hip-hop, few tales are as compelling as the saga of the Wu-Tang Clan, whose legacy reverberates 30 years since the release of their groundbreaking album, “Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).” This isn’t just an album; it’s a cultural milestone that encapsulates the raw and unfiltered experiences of nine young men from Staten Island, who channeled their struggles with poverty, violence, and racism into one of the most influential hip-hop albums ever conceived.

The Wu-Tang Clan, comprising the RZA, the GZA, ODB, Method Man, Ghostface Killah, Raekwon the Chef, Inspectah Deck, U-God, and Masta Killa, coined their home ‘Shaolin’ and forged a musical brotherhood that disrupted the smooth, melodic currents of West Coast gangsta rap with the gritty essence of East Coast hip-hop. Their music wasn’t just heard; it was felt, it was lived.

Marcus Evans, a Ph.D. student at McMaster University, dives into the depths of Wu-Tang’s cultural impact, exploring the symbiosis between their music and the martial arts films that profoundly influenced their artistry. The Clan’s adoption of the name ‘Wu-Tang’ was a testament to their affinity for these cinematic stories that resonated with their own narratives of oppression and resistance. RZA, the de facto leader, drew parallels between the histories of Asian and Black communities as depicted in these films, finding empowerment in the shared experiences of struggle and triumph.

The album’s title nods to classics like Bruce Lee’s “Enter The Dragon” and “The 36th Chamber Of Shaolin,” embedding the martial arts ethos into the very identity of the Clan. This influence is not merely thematic but also sonic. The opening track samples dialogue from the film “Shaolin and Wu-Tang,” setting the stage for an album that infuses the lyrical prowess of the group with the disciplined ferocity of martial arts.

As we celebrate the 30th anniversary of “Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers),” we acknowledge the album not only as a pillar of hip-hop history but also as a cultural phenomenon that continues to inspire and resonate with audiences worldwide. Marcus Evans’ scholarly pursuit to dissect and understand the depth of Wu-Tang’s influence is a testament to the enduring power of their music. The Wu-Tang Clan didn’t just enter the hip-hop arena; they revolutionized it, and their legacy is a testament to the art of storytelling through music, imbued with authenticity and the spirit of ‘Shaolin.’

Transcript :

ADRIAN MA, HOST:

Once upon a time, in a land called Staten Island, lived a group of young boys. Growing up, life was not easy for them. They faced poverty, violence and racism. But as these boys grew into men, they came to call their home Shaolin, and they would band together to form a musical brotherhood – a clan, if you will – with nine distinct members – the RZA, the GZA, ODB, Method Man, Ghostface Killah, Raekwon the Chef, Inspectah Deck, U-God and Masta Killa. And together they formed the Wu-Tang Clan. And their first album, “Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers),” released 30 years ago this week, is still considered one of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “C.R.E.A.M.”)

WU-TANG CLAN: (Rapping) Cash rules everything around me. C.R.E.A.M. – get the money. Dolla dolla (ph) bill y’all.

MA: So to talk with us about the impact and influences of this album, we’re joined by Marcus Evans. He’s a Ph.D. student at McMaster University currently writing his dissertation on Wu-Tang Clan and the influence of martial arts films on the music. Marcus, you’re literally a Wu-Tang scholar, so thank you for joining us.

MARCUS EVANS: (Laughter) Thank you for having me, Adrian. It’s an honor to be here.

MA: So we’ll come back to your scholarship on sort of the relationship between this group and the kung fu cinema influence. But just to start, can you take us back to 1993, the year that “Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)” was released? What, at the time, is the landscape of hip-hop?

EVANS: Sure. At the time of 1993 – and I’m recalling this from the experience of being a young kid in Mississippi – but it seemed to me that West Coast gangsta rap was really the dominant form. You know, I remember listening to Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic,” Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “Doggystyle” – really this kind of gangsta rap, this melodic form of rap, the kind of rap that made you want to get in a ’64 Chevrolet Impala and just ride out.

MA: The West Coast sound is dominant – right? – this sort of smooth, sparkly sound. Into that landscape drops “Enter The Wu-Tang,” and it’s not smooth. It’s, like, the opposite of smooth. It’s like…

EVANS: Exactly.

MA: How would you describe it?

EVANS: I mean, it was raw, gritty, dirty and it was just radically different from all of the West Coast music that I was familiar with.

MA: To understand the group, they decided to call themselves Wu-Tang. That name really stands out. So where, for them, does that come from, the desire to call themselves Wu-Tang?

EVANS: I think that, you know, for RZA and for the Wu…

MA: RZA being the sort of – the leader of the clan.

EVANS: Yeah. He’s the kind of de facto leader of the clan. For RZA and for the Wu-Tang Clan, watching these films gave them kind of images of other worlds, of something that was totally different from the experiences that they had in North America, in their urban environments. And RZA talks about this quite often. You know, he speaks about, yo, these films taught me something unique. It showed me that there was a history broader than the history that I ever learned about, being a Black American in the United States, right? He says, growing up as a kid, as a Black kid in America, I was always taught in school that, you know, we had a slave history, right? So these kung fu films for him resonated with him, in a way, because they told him about a kind of alternate history of Asian people who were, in some cases, like Blacks, suffering oppression. So he found these kind of cross-cultural parallels there between the martial arts films and his own world.

MA: When you think about this album, like, where do you hear that martial arts influence the most?

EVANS: One, I think just about the conceptualization of the album itself. The album “Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)” – of course, it borrows its title from at least two kung fu films. One is the Bruce Lee film “Enter The Dragon.”

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “ENTER THE DRAGON”)

PETER ARCHER: (As Parsons) What’s your style?

BRUCE LEE: (As Lee) My style? You can call it the art of fighting without fighting.

EVANS: Also, “The 36th Chamber Of Shaolin.”

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, “THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN”)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character, vocalizing).

EVANS: The second part of it really has to do with the sonic, you know, style. The very first thing that we hear on the album is a sample that comes from the film that basically informed the whole mythology of the Wu-Tang Clan, this film called “Shaolin And Wu-Tang,” the film out of which they formed their identity as the Wu-Tang Clan. And so the first thing that we hear on the track when we put in that CD or that tape – showing my age – we hear “Shaolin And Wu-Tang.” Shaolin shadowboxing and the Wu-Tang sword style. If what you say is true, then the Shaolin and the Wu-Tang is dangerous.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “BRING DA RUCKUS”)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: En garde. I’ll let you try my Wu-Tang style.

EVANS: And then we go into the songs. “Bring Da Ruckus,” to which that sample is attached, is a song wherein the lyrics are all about lyrical martial arts – deadliness, dangerousness, head chopping. I mean, several of these tracks on the album are all, in some ways, appealing to kind of form of martial arts that take shapes and the lyricism that the Wu was doing.

MA: Marcus Evans, thanks so much for joining us on ALL THINGS CONSIDERED. And good luck on your dissertation defense.

EVANS: Thank you, Adrian. It’s been a pleasure.

(SOUNDBITE OF WU-TANG CLAN SONG, “WU-TANG CLAN AIN’T NOTHING TA F’ WIT”) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

9(MDQ0ODU2MzU2MDE1NTM3MTIwMjFiMDhjNA000))

You must be logged in to post a comment.