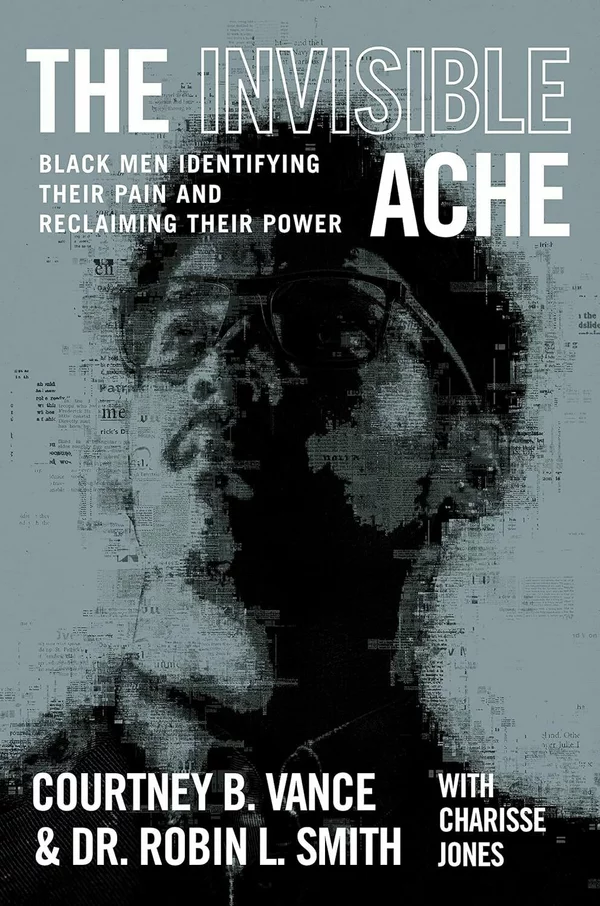

In the wake of these devastating losses, Vance has focused on peeling back the layers of both his father’s pain and his own struggles as a Black man in America. In a new book, The Invisible Ache, Vance and psychologist Robin L. Smith (who often goes by Dr. Robin) explore the trauma unique to Black men and boys, and address what they see as an urgent need to change the conversation about mental health.

“[With] Black boys and Black men, the rates of suicide is increasing,” Smith says. “The rate is accelerating faster than any other group in the country, in the United States. And so we have to ask why.”

Smith points to a modern culture of isolation and loneliness, which the surgeon general has referred to as a public health emergency. But, she adds, those factors are compounded for Black men and boys.

“If we then put race and racism with isolation and loneliness, surely we understand that Black boys and Black men are up against historical trauma as well as current-day trauma,” Smith says.

Though the book is focused on the mental health of Black boys and men, Vance says the issue has universal implications: “We are all interconnected. … My ache is your ache. If I’m aching, [and] you [are] clutching your purse as I walk by, you’re aching. You’re as much in a prison as I am,” he says.

So when you talk about stigma for therapy — that therapy is for white people, for rich people, for sick people — not only is that not true, therapy … at its best, it’s an opportunity to be in a safe space and [to] overhear the conversation that you’ve been having with yourself all of your life, but it’s never been safe to listen.

If … a Black boy ends up being chased or shot and killed, too often, this is about: How is it that Black boys are often seen as scary and dangerous, even when they are 6 or 7 or 10? The experience that the white world has of them is their skin color and their gender, [which], put together, creates a level of fear. So that person who I’m describing, who is pathologized and demonized, can ingest that as if those lies are true and then never expose and be treated for what it has cost them to be Black and male in America.

Transcript :

TONYA MOSLEY, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. Actor Courtney B. Vance’s decadeslong career spans across stage, film and television. But when he was a young actor in the ’90s on Broadway, he received a call from his mother that would tear his world apart. His father was dead, she said, by a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Years later, Vance’s godson, a young, promising college student, would succumb to the same fate. What transpired for Vance after these devastating losses has now become a lifetime of peeling back the layers of not only his father’s pain but his own struggles, too, as a Black man in America.

In a new book, “The Invisible Ache,” Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin Smith explore the trauma unique to Black men and boys and what they say is an urgent need to change the conversation about mental health. In the decades since Vance’s father died, rates of suicide and depression among Black men and boys have steadily risen to alarming rates.

Courtney B. Vance is an award-winning actor known for his roles in “The Hunt For Red October,” “The Preacher’s Wife,” FX’s “The People V. O.J. Simpson” and HBO’s “Lovecraft Country.” Dr. Robin L. Smith is a licensed psychologist, New York Times best-selling author and talk show host. She’s known for her regular appearances as the on-air therapist for “The Oprah Winfrey Show.” Dr. Robin Smith and Courtney B. Vance, welcome to FRESH AIR.

COURTNEY B VANCE: Thank you.

ROBIN SMITH: Our pleasure.

VANCE: Thank you.

SMITH: Thank you so much, Tonya.

MOSLEY: Well, both of you, thank you for writing this book. And, Courtney, I want to say I’m sorry for the loss of your father and your godson.

VANCE: Thank you. Thank you so much.

MOSLEY: I was just so struck reading your book. Right from the very start, you say that your dad suffered in silence, and that was not only devastating to learn, I know, I’m sure, but in many ways, it also felt familiar to you.

VANCE: Well, you know, I didn’t know him that well. He was at every event that I was in. I was three sport, all state at Detroit Country Day. I did – I was in every club, and somehow he and my mom were there, holding down their jobs, each of them. Him at the Chrysler benefits department and my mother, a librarian for 35 years, Detroit Public Libraries. But, you know, do we ever know our parents? You know, when we were – before we come out of the house? I – and I just knew that I was loved.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: There was no – I came out of that house not knowing, you know, them as well. It’s like my children kind of know us, but they don’t. You know, you begin to grow into knowing your parents as you grow as a young adult. So I just knew he was my hero, and he was the smartest man in the room and was able to talk on any topic, which was very intimidating to me.

MOSLEY: It was a generational thing, too, of not knowing your parents. But then this added layer of really what the name of the book is called, this invisible ache. He did not speak about his pain, the turmoil that he was going through. And, Dr. Robin, I heard you say that this title is like permission. It’s like a permission slip for Black men to acknowledge something that society doesn’t really open up space for. Can you say more about that?

SMITH: Yes. You know, we hear the old adage that silence is golden. We often don’t hear the times in which silence is deadly, because there is so much moving in the inner world of a person. And if they feel isolated, if they feel that there is no safe place to explore and express what’s going on inside, that manifests in lots of ways. And one of those could be suicidal thoughts. It could be thoughts that life is too much. And if you’re living in that silence and isolation by yourself, it can take you to very dark and scary places. The other thing I just want to point out when Courtney just shared about his parents and his father being his hero, his father is still his hero. His father did not lose his stature because he died by suicide. And I think it’s really important for us to know that when we understand that someone had a struggle that we didn’t know anything about, that we don’t need to punish them or ourselves for the mystery of what was unknown.

MOSLEY: I mean, what you’re saying here is an important distinction that I don’t think we often talk about and that’s the shame around suicide because it’s almost like a moral failing that we have put on it. I think you have changed the language even in the way that Courtney talks about it. Before you all got together, he was saying committed suicide. And you said, well, that language, we need to rethink that. In that, though, comes what you’re saying there of his father still being his hero.

SMITH: Yeah. I mean, and because committed suicide is like a crime. Suicide is not a crime. It’s an act of desperation. It’s an act of running out of steam and hope. We talk about that hope is an acronym that we use for hold on, pain ends. But, Tonya, if I don’t know that the pain is going to end, if I think whether I am a young Black boy or an older Black man, that there’s no way out except death to bring relief and release, the truth of the matter is that’s a prison of a different kind. And so it’s – the shame is so…

MOSLEY: Misdirected.

SMITH: Yes.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

SMITH: Thank you. It’s misdirected.

VANCE: When we have a worldwide situation like we did, I mean, that’s what exacerbated this discussion and this pandemic of suicide, especially with the young people and the children, as Dr. Robin will talk about. But we have to elevate our abilities and our need to – because otherwise, if we’re going to shame the individual, we need to shame the culture that allows it to – when the entire world shuts down because of something, do you not think there’s going to be a residual effect on the entire world, and especially the young people, that when you couldn’t have a graduation, when you couldn’t go to – you know, only 10 people would go to funerals and weddings and the emotional, spiritual and psychological effect of that needs to be discussed.

SMITH: Yes.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: And you can’t just go, oh, well, that – business as usual. Let’s go on. You just have to deal with it. And the repercussions of that is where we are now with the epidemic with suicide.

MOSLEY: Well, you know, I bet so many men are listening to this and saying to themselves, yep, this all sounds right. This sounds very familiar. But, Dr. Robin, what are some of the distinctions that set Black men and their pain apart? What do the stats tell us?

SMITH: Well, that Black boys and Black men, the rate of suicide is increasing. It’s not only that Black boys and men are dying at a higher rate, the rate is accelerating faster than any other group in the United States. And so we have to ask, what is it?

MOSLEY: Why?

SMITH: Yes…

MOSLEY: Yeah.

SMITH: …We have to ask why and what is it and how is there systemic realities inside of that number that Black children – we’re not just talking about teenagers or, you know, adolescents and young adults; we’re talking about Black children – are dying by suicide at a higher rate than any other group.

MOSLEY: Under 12 years old.

SMITH: Absolutely – under 12. We’ve got 8 year olds, 9 year olds, 10 year olds who have taken their life. And people will ask, how much does social media have to do with that? But what is bigger is, as Courtney just said, it’s the culture that is fostering this kind of isolation. You know, we’ve heard the surgeon general talk about loneliness and that he’s thinking about, because of the research, actually having loneliness as a public health…

MOSLEY: Emergency, yeah.

SMITH: …Emergency.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

SMITH: So if we then put race and racism with isolation and loneliness, surely we understand that Black boys and Black men are up against historical trauma as well as current-day trauma.

MOSLEY: You know, I can’t help but think, though, that holding space for Black men is also important in the scope of this very conversation because of this platform that we’re on, on public radio right now…

SMITH: Yes.

MOSLEY: …Which is a very white space, and we’re talking about a very Black topic. Some people might be listening right now and thinking, why is this important to me? Dr. Robin, what do you say to that?

SMITH: I love that question. What does this have to do with me? You know, Black boys and Black men – the ache that lives deeply embedded in Black boys and men is actually in every life, and it shows itself differently when one has been pushed to the margins. But you want to care about someone else because when it is your turn to need the care, to need the compassion, to need someone to mirror back the soul murder that happened to you.

VANCE: We’re talking about the ache – about Black men and young boys. But the ache was – we have to go back to slavery and how we’re all interconnected through that and that we – eventually, you’re going – we’re going to have to deal with each other. And so we’re talking about these aches, but my ache is your ache.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: And if I’m aching, you’re holding – clutching your purse as I walk by, you’re aching.

MOSLEY: Yeah. That’s so important.

VANCE: You know, you’re as much in a prison as I am.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, my guests are award-winning actor Courtney B. Vance and licensed psychologist Dr. Robin L. Smith. They’ve written a new book with writer Charisse Jones titled “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SOLANGE SONG, “WEARY”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. And today we’re talking to actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin Smith about their new book, “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power,” which explores the trauma unique to Black men and boys and the urgent need to change the conversation about mental health. I want to note that during this conversation, we are talking about acts of suicide and suicide ideation. If you are in a mental health crisis, help is available. 988 is the number of the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Courtney, this therapist that you went to, you refer to her as Dr. K in the book. It’s Dr. Kornfeld (ph). And the way that she got you to the place of being able to access yourself and your thoughts and your feelings and your pain – one of the first things she had you do was to write down your dreams, your literal dreams that you would have when you slept at night or however you interpret it. What was the significance of doing that?

VANCE: Well, the first thing – she asked me how I make decisions. And, of course, nobody ever – I’m 30 years old – no one has ever asked me. I don’t know, I flip a coin, and – right? Isn’t that what everybody does? And she just quietly listened and said, you know, Courtney, you know, that’s wonderful for acting, but in life, it can be devastating. You know, when you don’t know what to do, sometimes you should probably don’t do anything. And she said, Courtney, do you have – and this is over a series of meetings, of course. She said, Courtney, do you have the patience to let the mud settle in the water and the water become clear? And I said, oh, no, Dr. K, what are you talking about? Wait? Settle? Mud? Patience? I got to go, doc. I got to go. I mean, that’s – I’m an achievement-oriented young man at that time. I’m – I – and my achievement and my go-go-go-go-go-ness served me very, very well.

MOSLEY: Right.

VANCE: And so – but she’s just making mental notes. And then she said, Courtney – because the way we got together was through a dream. The night before I met Dr. Kornfeld, I had a dream and something about a pattern and, you know – and I went in, and I shook Dr. Kornfeld’s hand in the hallway. And I knew when I shook her hand – she’s about five feet from the ground. She was short and very motherly. And she said, you can – there’s an office, part of my office to the right. There’s a room there. And there was a couch, and on the couch was a pillow or something. And it had pretty much the same pattern as the pattern in my dream.

MOSLEY: Wow.

VANCE: And I said wow. And I told her, of course, like, you know, about that. And we, you know, I was talking a mile a minute in the session and she said, Courtney, you don’t have to tell me everything today…

MOSLEY: Just write it…

VANCE: …And just..

MOSLEY: …Down. Slow down.

VANCE: …Take your time.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: And gradually, you know, we had some more sessions, and she said do you dream? And I said, no, I mean, I don’t know, but I don’t remember them. She said, well, I’d like you to get your dreams. And that’s all she said.

MOSLEY: Well, you being the overachiever that you are…

VANCE: There it is.

MOSLEY: …Then set off to be the best dream catcher that you could be. You even started taking a class on dreams, but you started to write down your dreams, both your hopes and your dreams, but also your literal dreams that you were having. And what did that exercise do for you?

VANCE: It organized my day. It centered me. The basis of it was in order to get your dreams, you need simply a notebook, a pen or pencil and a flashlight. And then when you wake up, write down the first thing that comes to your mind. Initially, it’s just, you know, whatever. You know, it doesn’t have to be a dream. Just whatever. You’re training your mind to go where was I? And by the third night, they – whoosh. They came in, and I was getting five, six, seven, eight, sometimes nine dreams a night. And I would wake up and I would write down my dreams. And so that first week, I – they started to come in, I went to my session with Dr. K, and I said, there you go. Thirty-five dreams.

(LAUGHTER)

MOSLEY: And she’s like, wait a minute, hold on.

VANCE: She said you know what? You little – so she said, Court, just give me the most powerful one every week. This is how we’re going to work.

MOSLEY: What’s so powerful, Courtney, about you sharing this story – a couple of things. I was just thinking about the power of you writing your dreams out and then talking about them with someone in a safe space like you describe it. Like, all of the answers are inside of you. That’s the first thought I had.

SMITH: Yes. Yes. yes.

MOSLEY: And then – yeah. Then the second one is there’s such a stigma – and Dr. Robin, you can probably speak to this – not a stigma, but maybe a skepticism about therapy overall. And actually what happens in therapy, especially for Black men. Can you kind of talk about that? ‘Cause that is – that’s kind of maybe the one – one of the biggest barriers to seeking therapy.

SMITH: Yes. You know, I – when I think of the disservice that that messaging has perpetuated in men, and particularly Black men, that I don’t want anybody to get in my head, I don’t want anyone in my business, I don’t want anyone messing with my mind, I don’t need any of that ’cause I’ve got this, so all of those messages are conditioned responses to trauma and to dis and misinformation. If you understood that you were whole, and whole people need other people who are safe to explore their internal worlds, you wouldn’t need the defense that you don’t want anyone getting close. That’s really what we’re talking about. And so part of what Dr. K did and Courtney said yes to without even knowing what he was saying yes to, he was becoming familiar with his own inner world. He was becoming familiar with…

MOSLEY: With himself.

SMITH: Yes…

MOSLEY: Yeah.

SMITH: …With himself and with the unedited pieces of himself. Because so often – and this is true for all of us – we’re trying to gauge how much to say. We’re trying to gauge whether or not I will be judged or trashed or embraced for this thought. And so Courtney just said, with Dr. K, she had no judgment of what he was bringing or not bringing. She set the table and sent an invitation and said, Courtney, please come. And so when you talk about a stigma for therapy, you know, that therapy is for white people, for rich people, for sick people, not only is that not true, therapy – and what it is, I believe, Tonya, at its best, it’s an opportunity to be in a safe space and overhear the conversation that you’ve been having with yourself all of your life, but it’s never been safe to listen.

MOSLEY: Our guest today is award-winning actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin Smith. They have a new book out titled “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. I’m Tonya Mosley, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF KENNY BARRON AND DAVE HOLLAND’S “DR. DO RIGHT”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. And today I’m talking with actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin Smith about their new book, “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power,” which explores the trauma unique to Black men and boys and the urgent need to change the conversation about mental health. Courtney B. Vance is an award-winning actor known for his roles in “The Hunt For Red October,” “The Preacher’s Wife,” FX’s “The People V. O.J. Simpson,” and HBO’s “Lovecraft Country.” Dr. Robin L. Smith is a licensed psychologist, New York Times bestselling author and talk show host. She’s known for her regular appearances as the on-air therapist for “The Oprah Winfrey Show.” I want to note if you’re in a mental health crisis, help is available. 988 is the number of the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Well, Courtney, do you remember the first time you actually was told or heard man up or boys don’t cry or any sort of message that told you sharing your emotion in this way is not what boys do?

VANCE: I don’t remember that. You know, I’ve heard it. But I was a very emotional young child, and I had an older sister two years older. And so, you know, we grew up in a Black community, and we just played and had fun and, you know? And so I don’t remember that. You know, in the context of that, I know my father and I only would and could talk about certain things. I knew – you know, you know your household. You know what you can ask and what you can’t ask. But, you know, my father was always there. I mean, he loved tools. He loved going and fixing the car. In that context, I knew the tools to be able to hand to him, but I didn’t – it wasn’t explained to me what he was doing. But I knew the hex nut. I knew the Phillips and the straight. I mean, I knew all the tools. But…

MOSLEY: But feelings.

VANCE: No.

MOSLEY: Did you talk about feelings?

VANCE: No, no.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: That’s – that was – and especially for him because – that – he didn’t have the tools.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: He had the tools. He knew where the tools were at Sears.

MOSLEY: Yes.

VANCE: But he didn’t have the life tools.

MOSLEY: Courtney, I want to talk to you for a moment about intergenerational wounds and how they might show up in the day to day. You were actually on PBS’ “Finding Your Roots” a few years ago, and you found out some really interesting things about your family. But what did you find out that helped you understand more about maybe the pain that lived within your father?

VANCE: Well, my father’s side of the family found us – in Chicago. And they reached out to my sister and I. And we – my sister and I went to Chicago and met a good portion of our Vance side of the family. And it was very moving, very emotional, very fun, very lively, very – just like, you know – oh, I can’t even describe how – you know, we were just – everyone was just giddy. And then, you know, they were just talking – they started talking about – you know, because we never knew who my father’s mother was.

MOSLEY: Because he was in foster care.

VANCE: ‘Cause he was foster care.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: So he would never talk about it. My mom said he would never. But, you know, his mother – the family was telling us that – Ardella was her name – and Ardella would periodically, you know, say – little, short lady, five feet from the ground, unlike Dr. K – she would say, my boy, where’s my boy? ‘Cause she was – you know, after the trauma, she was institutionalized and sent back down to Arkansas from Chicago.

MOSLEY: Where she was from.

VANCE: Where she was from. She had two boys. And evidently, on the birth certificate of her oldest son, Larry, they had back in the day – maybe they still do have on the birth certificate, you know, space for you to put down how many stillbirths you had, how many stillbirths the mother had. And there was a six there.

MOSLEY: Oh.

VANCE: And she had Larry when she was 15. So she had been raped, molested since she was 9 and so lost her mind and then had my father two years later at 17. And then, you know, there’s a whole other story around that. I’m not going to go into it. But she was saying that the family was telling us that periodically she would say, they took my boy. They took my boy. Where’s my boy? Where’s my – and they wouldn’t know what she was referring to. So they would just say, oh, Nana, stop now. It’s OK. It’s OK. But the oldest son, Larry, was raised by Ardella’s sister, as her own child. And he didn’t.

MOSLEY: So he part of (inaudible)…

VANCE: Yeah. He didn’t find out that that wasn’t his mommy until he was 17, 18, 19 years old.

MOSLEY: Wow.

VANCE: OK? But there was nobody left to take in Conroy. And so that – he was put in the foster system. And, you know, so I’m sure the shame within the family of what they had done to – and lost him. He was lost. So my father did his best and did amazingly well, you know, with – by being thrown away. But if he had been able to hold on, he would have been with us when we went to Chicago.

MOSLEY: And he would have found out that information.

VANCE: He would have found out what his mommy was looking for him.

MOSLEY: That his mother actually didn’t throw him away…

VANCE: Right.

MOSLEY: …That it was the circumstance.

VANCE: Yeah.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, my guests are award-winning actor Courtney B. Vance and licensed psychologist Dr. Robin L. Smith. They’ve written a new book with writer Charisse Jones titled “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHARLIE HADEN’S “EL CIEGO (THE BLIND)”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR, and today I’m talking to actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin Smith about their new book, “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power,” which explores the trauma unique to Black men and boys and the urgent need to change the conversation about mental health. I want to note, during this conversation, we’re talking about acts of suicide and suicide ideation. If you’re in a mental health crisis, help is available. 988 is the number of the suicide and crisis lifeline.

In the through line of your story, there is this very tragic thing that happens to you as an adult, as a man. But in me putting together you growing up in Detroit, I just want you – if you can just give me just a little bit of a lens on how that invisible ache might have been growing inside of you until this moment that you came to where you felt like you really needed to seek therapy.

VANCE: My family was completely focused on education and achieving, and that’s wonderful. We were in a Black environment, 12th Street, Detroit. My father was a manager of one of the first supermarkets in Detroit, BI-LO.

MOSLEY: What was it?

VANCE: BI-LO.

MOSLEY: BI-LO. OK. Yeah.

VANCE: And of course, during the ’67 riots, they burned it to the ground, and so he had to pivot. And that’s when he went to Chrysler – foreman – and elevated to – into benefits and, you know, achieving and doing well. And of course, you know, life happens where all of a sudden, you’ve – we’ve got you this in this wonderful position, but now we need you, Mr. Conroy Vance, to do the dirty work. We need you to fire 3,000 people in this plant, and then we need you to rehire 3,000 more ’cause we’re doing a transition to a new – you know, the business of life, hiring, ruining people’s lives. We want you to be able to do that.

And then, you know, after you’ve done those two things, we may or may not need you anymore. And he got wind of that, that – just the thinking that you’re all of that and that you’re in the club. You finally made it, and all of a sudden, you’re not. And realizing that as a Black person, that – you know, and we teach this to our young people, that you have to be – and my father told me, he said, don’t get caught up in – you know, over there at Harvard. Those young white kids will cut their hair, and then they’ll go into their father’s businesses. And you’re thinking that you’re one of them. You’re – they’ll take care of you, or you’re their buddies. And all of a sudden, they’re gone, and you’re left with nothing. So take care of yourself. Focus. Keep working. Work twice as hard. And that’s a message that, you know – and you – then you talk about, you know, teaching young Black boys about how they deal with the police.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: You know, those are things that we internalize. And the high cost of high living or low living is that. How do you go back and recover? How do you – without knowing about – that I even need to talk to somebody? How do you go back and deal with the fact that when we first moved into La Quinta (ph), that the police were outside my house, the twins were 3, sleeping, and they put me on my knees in front of the house as I came out the door at midnight looking for a package on the front stoop.

MOSLEY: And at this point, you are Courtney B. Vance, the accomplished actor.

VANCE: I’m a Black man who doesn’t – you know, the skin color. So, you know, it’s – you know, you really have to – I mean, I read, Tonya. I read biographies, lots of them. And I read them because I want to see how other people tried, failed, succeeded, and do a comparison – how did Lincoln do it? How did Frederick Douglass do it? How did Malcolm X do it? How did MLK do it? – and start to get a composite and start to realize that they all were in prep mode for now, that 30 years ago, they were getting ready for when it was – they were tapped on the shoulder.

At what point do you not realize that you’re – as Dr. Robin says, you’re being prepared for greatness? You’re in prep mode now. You’re studying now for when your shoulder is tapped. And if you haven’t done the work, then the tap is going to move on to someone else’s, and you’ll go a different way. I want to go higher. In order to do that, I’ve got to go – there’s bishop – our Bishop Blake told us years ago when we were building the cathedral, there’s a mathematical formula for as high as you want a building to go, you have to go a certain amount of feet deep. And if you want to later on try to add to the height, you cannot do it. You have to tear that building down and go deeper into the ground. So there’s – if you want to go higher, you must go deeper, and I want to go higher.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: And it’s going to cost me something. Everything that’s worth doing costs you something. And just because you’re – it’s hard work doesn’t mean there’s something wrong. It just means that there’s work. You got to go through it.

MOSLEY: Courtney, there are these other ways to access healing. Both you and Dr. Robin have talked about a couple of them in the book, but I was thinking about acting for you because acting does give you access to these emotions. You have to access these range of emotions in order to emote. Do you see that as a form of therapy in a way?

VANCE: Acting saved my life. I didn’t know anything about acting. I was – I didn’t know what I wanted to study. And I was running track. You know, I was a hurdler, and – but then I realized I’m not doing what I said I would do, which was meet people. And from meeting people, I would find out what I needed to do. And I said, let me do theater. And I came back my sophomore year, and I started doing plays. And after my second play, I – my aunt said, you could do this, Courtney. And so – and – but acting was voices for me. It was just – I thought it was – that’s what I thought it was. And then I did…

MOSLEY: Like impersonations, almost. Yeah.

VANCE: Impersonations and just – you know, and my voice was, you know, had a wonderful voice, blessed. But while I was doing one of the plays at the mainstage called “Lulu” with – Lee Breuer’s “Lulu” with Kathy Slade and others, and Kathy said, Courtney, you should go to – you know, reach out to Tina Packer at Shakespeare & Company. And they have Ford Foundation scholarships, and you get free class work for cleaning the grounds. And I said, really? So I went up there, auditioned at Edith Wharton’s estate, and I got it. And I told my girlfriend at the time, and she got in. And we went up there, and so we, you know – I’m still with the voices thing. And so 15 or 16 of our apprentices were, you know, around, and we were – you know, one evening, all the company got together.

And Tina said, all right – because she’s English. All right, people, the apprentices gather. And I want you all come up on the stage and one by one come up, and I want you to tell us two things about yourself you want us to know. And we were all like, oh, that’s very cool. I’m so excited. I’m so excited. They want to – and then she said – and so we thought she was done, she said, and I’d like you to tell us then two things you don’t want us to know about yourself. And I said, wait a minute, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait a minute. That’s not – what is – this is not acting. This is too much for me. And so…

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: …It was something I couldn’t figure out. And it drove me, you know, a shifting was happening. If I wanted to do this acting thing, I had to shift my mind. There was one night I just couldn’t do it, Tonya, couldn’t figure it out. I couldn’t – and I had to go out on the road and scream. And we were in the woods at the Mount, and we were just deep in the woods. And I’m afraid of the dark. I conquered my fear, came outside and felt my way, you know, the quarter a mile, a half mile to the road and ran down a mile down the road. Got a stop sign and shook it from its – and shook it down. I was so – and I screamed, you know? And so I said, oh, God, OK, I’m better, and I’m better now. So I came back…

MOSLEY: Oh, I bet that felt good, though, too.

VANCE: It felt so good. I came back to the, you know, to the woods and felt my way back into the – to the Mount and to the, you know, stables where we were staying and went to sleep. Got up the next morning, we were down in the dance studio where we do our warm ups with our voice teacher. Hum hum. I do all of the touching sound, as we called it. And, you know, as I was laying there – touching sound, I overheard somebody, you know, a couple of my apprentices saying, did you hear that last night? Did you hear that moose out there scream? You heard that?

MOSLEY: It was you.

VANCE: It was me. And I was like…

MOSLEY: It was you.

VANCE: …Oh, my goodness, they heard me.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

VANCE: So, you know, I had to shake myself and get into another head. And that – once I made that transition there, the next summer, we were doing the balcony scene of Romeo and Juliet. Oh, blessed, blessed night. All this is but a dream. Too flattering sweet to be substantial. As I’m saying the lines, it all rushed – the emotion came through me on the line and everyone went something just happened. Something just happened. Courtney, what – and I was like, it just – I got what they were saying. The acting thing began for me when that – but it was a shifting of the head, and that’s what is hard for all of us to do is to get our minds around a different thing, and what does it take for us to make that shift in our thinking in order for the emotion to come through?

MOSLEY: Dr. Robin and Courtney, there is a final message in the book that I keep thinking about, and it’s the list of questions that you’re asking the reader to ask themselves. Courtney, would you mind reading?

VANCE: (Reading) Where does it hurt? What do I tell myself about me? Whose voice do I hear? Who is the real me?

MOSLEY: Dr. Robin, these are important questions you feel like every Black man should ask himself.

SMITH: Yes. And should ask his son, his daughter. But it has to start with the self. Yes. Those are the essential questions that call you into this moment. One of the things Courtney and I say about “The Invisible Ache” is that it’s like an old-fashioned altar call where we are inviting all Black boys and men and those who love them to come on down, to come to the forefront of their lives.

MOSLEY: Dr. Robin Smith and Courtney B. Vance, thank you for this conversation.

SMITH: Thank you, Tonya, so much.

VANCE: Thank you for setting the table.

MOSLEY: Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin Smith co-authored the book “The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain And Reclaiming Their Power.” Coming up, Kevin Whitehead reviews a new album from jazz pianist Angelica Sanchez. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF TOMMASO AND RAVA QUARTET’S “L’AVVENTURA”) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

9(MDQ0ODU2MzU2MDE1NTM3MTIwMjFiMDhjNA000))

You must be logged in to post a comment.